Jessie Redmon Fauset and Countee Cullen

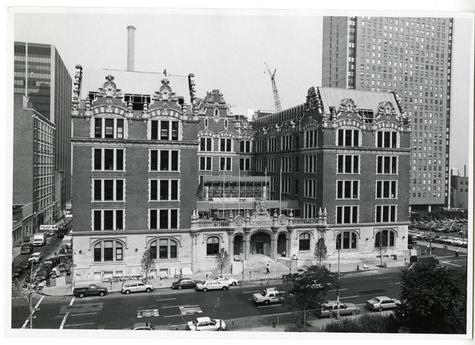

Image source: John Jay College Archives, Lloyd Sealy Library, John Jay College of Criminal Justice, CUNY. Digital Collections.

When John Jay College of Criminal Justice moved into Haaren Hall, it was the third school to occupy the building. The H-shaped edifice, designed by Charles Snyder, was built in 1906 to house DeWitt Clinton High School. When DeWitt Clinton moved to the Bronx in 1927, the building was then occupied by Haaren High School until a merger with Park West High School in the late 1970s. After that, the building languished, empty for years until 1985, when it was briefly slated to become a telecommunications center called the “Metropolis,” which would feature two 30-foot-high indoor waterfalls. John Jay College moved into the building in 1988 after giving it a thorough gut-renovation.

If these walls could talk, they would tell of a century-long history of academia, of the thousands of graduates of the three schools. And they might tell of two notable Harlem Renaissance writers who roamed the old halls of DeWitt Clinton.

Jessie Redmon Fauset (1884-1961)

Considered by many to be Fauset’s best novel, Plum Bun (1929) features a light-skinned young black woman who moves to New York City and decides to “pass” as white. She enters the world of white society, succeeding socially and professionally where she would not have been able to if recognized as black, but she struggles in her relationship with her darker-complected sister. Plum Bun was written while Fauset taught at DeWitt Clinton. The novel is included in Harlem Renaissance: Five Novels of the 1920s, which can be requested in the catalog from Brooklyn College.

The Chinaberry Tree (1931) tells the story of a young woman struggling with her “bad blood,” as her community refers to her mixed parentage. The novel depicts interracial relationships in a small-town environment haunted by secrets and prejudices. (John Jay Stacks PS 3511 .A864 C48 1995b; catalog record).

Image source: Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Photographs and Prints Division, The New York Public Library. "Jessie Fauset, author." The New York Public Library Digital Collections. Link.

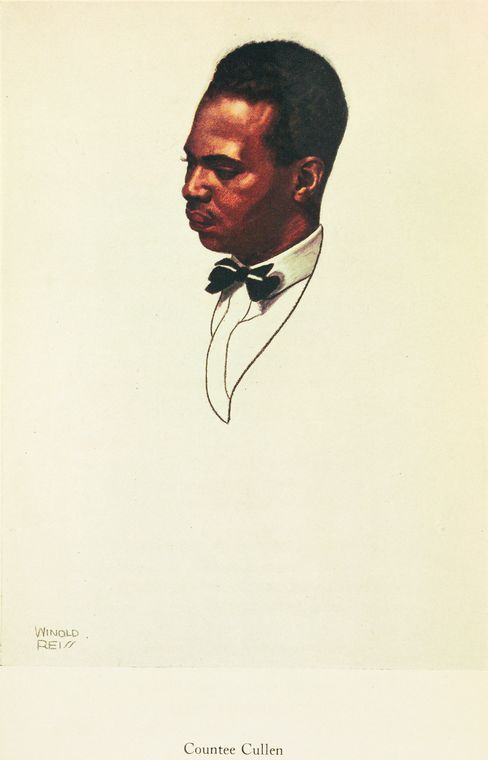

Countee Cullen (1903–1946)

Cullen’s best-known poems are collected in On These I Stand (John Jay Stacks PS 3505 .U287 A6 1947; catalog record). See p. 3 for what is arguably Cullen’s most quoted poem, “Yet Do I Marvel,” and pp. 104–137 for “The Black Christ,” which was warmly praised by The New York Times Book Review in 1929.

More of Cullen’s writing, including a novel, essays, speeches, and an interview, is collected in My Soul’s High Song (John Jay Stacks PS 3505 .U287 A6 1991; catalog record). See p. 325 for “Life’s Rendezvous,” for which Cullen won a citywide poetry contest while he was still attending DeWitt Clinton.

Image source: Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division, The New York Public Library. "Countee Cullen." The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1925. Link.

References

- “Cullen, Countee.” Encyclopedia of African-American Culture and History. 2nd ed. 2006.

- “Fauset, Jessie Redmon.” Encyclopedia of African-American Culture and History. 2nd ed. 2006.

- Nash, E. “F.Y.I.” The New York Times 16 Dec. 2001. (Brief history of Haaren Hall.)

- Shucard, A. Countee Cullen. Boston: Twayne, 1984. (Available as ebook and at John Jay Stacks PS 3505 .U297 Z88 1984; catalog record.)

Robin Davis